Wall Street Journal | Sarah Kent and Georgi Kantchev | July 28, 2018

Dearth of investments in oil projects mean a spike in prices above $100 could be on the horizon

Crude across the globe is being used up faster than it is being replaced, raising the prospect of even higher oil prices in the coming years.

The world isn’t running out of oil. Rather, energy companies and petro-states, burned by 2014’s price collapse, are spending less on new projects, even though oil prices have more than doubled since 2016. That has sparked concerns among some industry watchers of a price spike that could hurt businesses and consumers.

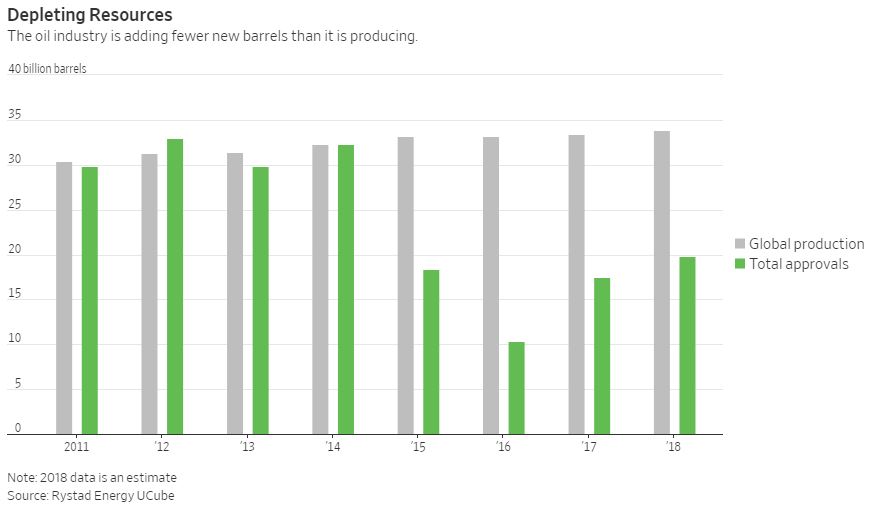

The oil industry needs to add 33 billion barrels of crude every year to satisfy anticipated demand growth, particularly as developing countries like China and India are consuming more oil. This year, new investments are set to account for an increase of just 20 billion barrels, according to data from Rystad Energy.

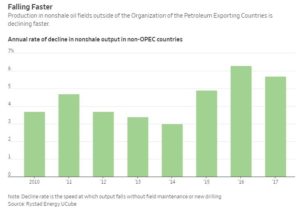

The industry’s average decline rate—the pace at which output falls in a particular field or region without new investment—was 6.3% in 2016 and 5.7% last year, the Norway-based consultancy said. In the four years before the crash, that decline rate was 3.9%.

Any shortfall in supply could push prices higher, similar to when oil hit nearly $150 a barrel in 2008, some industry participants say.

Any shortfall in supply could push prices higher, similar to when oil hit nearly $150 a barrel in 2008, some industry participants say.

“The years of underinvestment are setting the scene for a supply crunch,” said Virendra Chauhan, an oil industry analyst at consultancy Energy Aspects. He believes a production deficit could come as soon as the end of next year, potentially pushing oil above $100 a barrel.

Strong demand for crude could falter if the global economy slows. On the supply side, some large new projects have been commissioned, potentially signaling appetite for more investment, and companies are driving down project costs, allowing them to do more for less. Likewise, soaring production from U.S. shale fields has offset underinvestment and declines elsewhere. But the shale industry’s growth is expected to peak in the early to mid-2020s, according to industry experts.

Once, market participants worried that supply would peak. Now, they talk of vast oil reserves underground.

The Gulf of Mexico, for instance, holds roughly 4 billion barrels of proven reserves, according to 2016 data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. But new projects generally require billions of dollars of investment and years of development. BP PLC’s $9 billion Mad Dog 2 development in the Gulf of Mexico isn’t expected to start production until 2021, despite getting the green light in 2016. Such deep-water projects take an average of 3½ years and roughly $5 billion to go from approval to production, according to consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

The industry has a record of boom-bust spending that can lead to big price swings.

Read the full story here.